Evolutionary Solvers: Selection

March 4, 2011

This is the third post in a series on Evolutionary Solvers.

Biological Evolution proceeds by Natural Selection. The ruthless force identified by Darwin as the arbiter of progress. Put simply, Natural Selection affects the direction of the gene-pool over time by regulating who gets to mate. In extreme cases mating is prevented because a specific genome is so unfit that the bearer cannot survive until reproductive age. Another rather extreme case would be sterility. However, there’s a myriad ways in which Natural Selection can make it difficult or impossible for certain individuals to pass on their genetic footprint.

However, Natural Selection isn’t the only game in town. For a long time now humans have been using Artificial Selection in order to breed specific characteristics into a (sub)species. When we try to solve problems using an Evolutionary Solver, we always use some form of artificial selection. There’s no such thing as sex or gender in the computer. The process of selection is also much simpler than in nature, as there is basically only one question that needs to be answered: Who gets to mate?

Allow me to enumerate the mechanisms for parent selection that are available in Galapagos. This is only a small subset of the selection algorithms that are possible, but they seem to cover the basics rather well.

First off, we have Isotropic Selection, which is the simplest kind of algorithm you can imagine. In fact, it is the absence of a selection algorithm. In Isotropic Selection everyone gets to mate:

No matter where you find yourself on this fitness graph, your chances of ending up in a mating couple are constant. You might think that this is a particularly pointless selection strategy as it does nothing to further the evolution of the gene-pool. But it is not without precedent in nature. Take for example wind-pollination or coral spawning. If you’re a sexually functioning member of such a species, you get to play ball come mating season. Another example would be females in a walrus colony. Every female in a colony gets to breed with the dominant male, no matter how fit or unfit she is. Isotropic Selection is certainly not without function either. For one, it dampens the speed with which a population runs uphill. It therefore acts as a safe-guard against a premature colonization of a local -and possibly inferior- optimum.

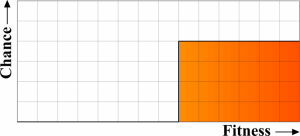

Another mechanism available in Galapagos is Exclusive Selection, where only the top N% of the population get to mate:

If you’re lucky enough to be in the top N%, you’ll likely have multiple offspring. A good analogy in nature for Exclusive Selection would be Walrus males. There’s only a few harems to go around and far too many males to assign them all (a harem of one female after all is not really a harem). The flunkies get to sit on the side-line without a single chance to father a walrus baby, doing whatever it is walruses do when they can’t get any action.

Another common pattern in nature is Biased Selection, where the chance of mating increases as the fitness increases. This is something we typically see with species that form stable couples. Everyone is basically capable of finding a mate, but the really attractive individuals manage to get a lot of hanky-panky on the side, thus increasing their chances of becomes genetic founders for future generations. Biased Selection can be amplified by using power functions, which have the effect of flattening or exaggerating the curve.

May 19, 2014 at 21:48

Hi, I’m trying to use Galapagos in part of a lesson on evolutionary computation. I understand the different selection mechanisms you explain here, but I can’t see how to actually choose to change the selection mechanism in Galapagos. Do you have a blog post on that or can you explain how to do that?

December 21, 2019 at 19:17

Hi you have a wonderful Posting site It was very easy to post fantastic